Rev. J.J. Tompkins was born in Cape Breton’s Margaree Valley on September 7, 1870. “Jimmy’s” upbringing centered on family, faith and farm. He came to believe in the power of ideas and the need to instill them into the hearts and minds of the common working men and women of Nova Scotia.

Rev. J.J. Tompkins was born in Cape Breton’s Margaree Valley on September 7, 1870. “Jimmy’s” upbringing centered on family, faith and farm. He came to believe in the power of ideas and the need to instill them into the hearts and minds of the common working men and women of Nova Scotia.

Tompkins was a good pupil and by 1888 he had enrolled in the ‘high school’ program at St.F.X. He graduated from St.F.X.’s college program in 1895 and the following year joined the faculty. After teaching for a year, Tompkins answered the call to the priesthood and left, at the age of 27, for the Urban College in Rome where he was ordained in 1902. He was appointed to St.F.X. that year and became vice-rector (vice-president) in 1906.

From the 1890’s, economic stagnation gripped Atlantic Canada, causing massive out-migration, mostly to New England. At St.F.X., Tompkins urged the benefits of cutting edge scholarship, high educational standards,, and Catholic ethical principles. He believed all these should be applied to solve the problems of a depressed rural society. Tompkins built upon and amplified the work of other faculty members. He was also influenced by trends and developments in the wider world. He read about the struggle of Irish Catholics to develop a first class university system. In 1912, he attended the Congress of Universities of the Empire in England and heard firsthand about adult education programs in Britain and the U.S. Their adult education techniques fired his imagination with new possibilities for St.F.X.

In 1914, Tompkins met members of the Carnegie Corporation, the organization entrusted to dispense the immense fortune of the US industrialist Andrew Carnegie. Tompkins requested support for a chair in French at St.F.X. to provide educational leadership for the Acadians, and in 1919 the Corporation acceded. Meanwhile, in 1918, a new column entitled For the People appeared in The Casket, the local paper, featuring articles Tompkins either wrote or solicited. Between 1918 and 1921, he coordinated educational and social conferences at St.F.X.; the participants wrestled with topics such as agricultural reform, educational theory, housing, and leadership development. At the end of the war in 1918, social change and upheaval were in the air. Tompkins believed the war’s aftershock would serve to abolish the social and economic torpor of the Maritimes.

Tompkins’ famous 1921 pamphlet Knowledge for the People: A Call to St. Francis Xavier’s College, expressed his vision for social reform. The pamphlet challenged St.F.X. University and the wider community to work at reversing economic decline and out-migration. He called for better-trained professors at St.F.X.; his vision of the university’s role in adult education was to bring it to the people and ask, “How can we be of service to you?”

In 1921, Tompkins conceived another project: a “people’s school.” The first one was held at St.F.X. and was open to all. In January 1921, 52 young and middle-aged men, mostly farmers, came to the campus for classes on topics such as English, chemistry, physics, business, public-speaking, animal breeding and crops. Subsequent People’s Schools were held in 1922 and 1923. They received much praise and media coverage; observers expressed enthusiasm and hope for the promise of university extension work.

When Tompkins was writing Knowledge for the People, the Carnegie Corporation was surveying all Maritime universities to recommend improvements in their academic quality and funding. The foundation’s report urged university federation in Halifax; Tompkins and most of the clerical St.F.X. faculty voted to support it. The concept, however, faced stiff opposition from the St.F.X. president, Rt. Rev. Dr. H.P. MacPherson and Tompkins’ superior, Bishop James Morrison, who was also the chancellor of the university. Bishop Morrison, conservative and cautious, opposed the merger idea fearing that St.F.X. would lose its Catholic character. By the fall of 1922 the Board of Governors voted against it. The bishop, seeing no change in Tompkins’s unrelenting advocacy of it, and wishing to end the controversy, used his authority and removed him from St.F.X. Tompkins who had been working in university administration for over 15 years, and with no pastoral experience, was assigned as pastor to Star of the Sea Parish in Canso, Nova Scotia. The appointment proved providential.

Tompkins witnessed extensive poverty and substandard educational levels in Canso. In January 1923, shortly after arriving, he preached a sermon in Little Dover that expressed his solidarity with the poor fishermen. Over the next three years, he earned their respect and trust as he talked to them on the wharves and in their homes. He repeatedly criticized the lack of practical engagement by the church and the government.

Canso received national attention in July 1927 when the fishermen held a meeting to protest their desperate conditions. Tompkins helped to organize the meeting and convinced newspapers to report on their plight. He exploited the heightened public interest in his usual energetic fashion. He wrote to government officials and rallied his fellow priests to pass a resolution calling for a government commission. The MacLean Commission (struck in October 1927 and reporting in July 1928) delivered the first serious socio-economic analysis of the impact of industrialization on the Maritime inshore fishery. One important recommendation called for a government-paid worker to help organize the fishermen; Rev. Dr. Moses Coady would fill the post. By the end of Tompkins’ twelve-year stint in the Canso-Dover parish, he had helped establish credit unions, canneries and co-ops. He also coaxed the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Martha to begin social work in 1933; they stayed for 50 years. As well, he distributed reading materials from his glebe house library.

In 1935, Tompkins was appointed to the parish of St. Joseph’s, Reserve Mines, Cape Breton. Reserve Mines, a coal mining community, was gritty and poor. While the St.F.X. Extension Department had organized study clubs and a credit union, they had floundered. Tompkins decided that books and the ideas they contained would be the tools to break the cycle of dependence and poverty. Shortly thereafter, he opened the People’s Library in the parish rectory’s spare room. Tompkins purchased books on popular topics and the response was overwhelming, for the parishioners had a thirst for knowledge. Tompkins had once said that ‘ideas have feet’ and here he saw them run. The library featured the first full-time, paid professional school librarian in Nova Scotia. In 1940, Nova Scotia passed legislation creating a regional library system that was initially assisted by the Carnegie Corporation.

At the same time, Tompkins sought a solution to the miners’ grim and expensive company houses. He enlisted the aid of an American housing expert, Mary Ellicott Arnold, and helped the miners organize a housing co-operative. Tompkinsville, a new housing tract of 11 houses, was opened in August 1938.

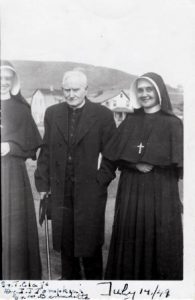

Tompkins passed away on May 5, 1953 and is buried in the St. Joseph’s Parish cemetery. During his life Tompkins received many accolades, including honorary degrees from Dalhousie (1919) and Harvard (1941). Rev. James Tompkins was a small man with big ideas. His curious, discerning, restless and energetic mind flung out ideas like sparks from an anvil. His ideas caught fire because he connected with the common people and the educated alike, prodding and provoking both to act. Thus, his many accomplishments have stood the test of time and monuments to his peculiar genius are still with us today.