Early Development

The situational elements discussed above–the Irish and Scottish Catholic parishioners and their priests, the Diocesan university, and the Scottish Catholic Society of Canada–facilitated the emergence of the Antigonish Movement over the 20 years between 1910 and 1930. This development can be divided into two stages. In stage one, priests from across the diocese learned about adult education and extension ideas and implemented these techniques themselves. In 1912, J.J. (Father Jimmy) Tompkins, St. F. X. vice rector and a member of the St.F.X. faculty, was in England gleaning information about extension and adult education techniques. Another St.F.X. priest-professor, Dr. Hugh “Little Doc” MacPherson worked with local farmers and provincial agricultural representatives to improve growing and marketing techniques and to implement cooperative practices.

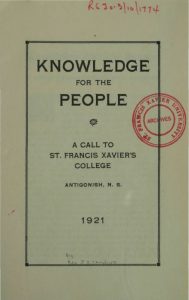

The situational elements discussed above–the Irish and Scottish Catholic parishioners and their priests, the Diocesan university, and the Scottish Catholic Society of Canada–facilitated the emergence of the Antigonish Movement over the 20 years between 1910 and 1930. This development can be divided into two stages. In stage one, priests from across the diocese learned about adult education and extension ideas and implemented these techniques themselves. In 1912, J.J. (Father Jimmy) Tompkins, St. F. X. vice rector and a member of the St.F.X. faculty, was in England gleaning information about extension and adult education techniques. Another St.F.X. priest-professor, Dr. Hugh “Little Doc” MacPherson worked with local farmers and provincial agricultural representatives to improve growing and marketing techniques and to implement cooperative practices.  In 1913-14, priests and some lay people engaged in a campaign of letter writing and public meetings intended to promote economic development that came to be called the Antigonish Forward Movement. Starting in 1918, a column entitled “For the People” appeared in The Casket. The same year, the Educational Conferences, a series of three annual meetings of diocesan priests, began. Their agendas touched on rural education and extension work. In 1920, the second conference witnessed the creation of the Educational Association that decided to “propagate Christian Social Principles and encourage the necessary means for their application, especially through the establishment of study clubs and publicity through the press.” Both the conferences and the Scottish Catholic Society of Canada had the support of Bishop James Morrison. In 1921, publication of Father Jimmy Tompkins’ famous pamphlet “Knowledge for the People” and the successful hosting of the first People’s School at St. F. X. furthered the cause of adult education and extension work in the district. Another tributary into the confluence of events and forces leading to the Movement was the debate about Maritime university federation. In the early 1920’s, the Carnegie Corporation of New York was invited to prepare a survey of the educational systems in Atlantic Canada. The 1921 Learned-Sills Report, which called for a merger of Maritime universities at Halifax, sparked a great deal of controversy throughout the diocese and around the province. In 1921 and 1922, debate raged between the pro and anti-merger forces. By the fall of 1922, however, the issue was decided for St.F.X. when its Board of Governors voted the plan down. Father Jimmy Tompkins, a friend and keen supporter of the Carnegie Corporation and its federation proposal, was one fall-out from the controversy. Bishop James Morrison, exasperated by his continued agitation for university federation, removed him from St. F. X. to run a parish in the fishing village of Canso. Tompkins’ presence there would later pay dividends for both the fishermen of Canso and the Antigonish Movement; however, the immediate result of the end of the federation debate was a temporary cessation of agitation for university extension work during the ‘cooling off’ period that followed. The federation controversy and involvement of the Carnegie Corporation also played a secondary, serendipitous role. On the eve of a trip to Truro to attend a meeting of the Nova Scotia Teachers Association, Rev. Dr. Moses Coady dined with the authors of the Learned-Sills Report in Antigonish. Kenneth C.M. Sills and William S. Learned told Coady they thought education was extremely important which helped change Coady’s attitude toward the association and strengthened his resolve to support it. Coady went to the meeting and talked himself into a job as organizer for a revitalized union and founding editor of its newsletter. His three-year stint with the teachers union raised his profile and improved his organizing skills; both things would be critical to his future leadership of the Antigonish Movement.

In 1913-14, priests and some lay people engaged in a campaign of letter writing and public meetings intended to promote economic development that came to be called the Antigonish Forward Movement. Starting in 1918, a column entitled “For the People” appeared in The Casket. The same year, the Educational Conferences, a series of three annual meetings of diocesan priests, began. Their agendas touched on rural education and extension work. In 1920, the second conference witnessed the creation of the Educational Association that decided to “propagate Christian Social Principles and encourage the necessary means for their application, especially through the establishment of study clubs and publicity through the press.” Both the conferences and the Scottish Catholic Society of Canada had the support of Bishop James Morrison. In 1921, publication of Father Jimmy Tompkins’ famous pamphlet “Knowledge for the People” and the successful hosting of the first People’s School at St. F. X. furthered the cause of adult education and extension work in the district. Another tributary into the confluence of events and forces leading to the Movement was the debate about Maritime university federation. In the early 1920’s, the Carnegie Corporation of New York was invited to prepare a survey of the educational systems in Atlantic Canada. The 1921 Learned-Sills Report, which called for a merger of Maritime universities at Halifax, sparked a great deal of controversy throughout the diocese and around the province. In 1921 and 1922, debate raged between the pro and anti-merger forces. By the fall of 1922, however, the issue was decided for St.F.X. when its Board of Governors voted the plan down. Father Jimmy Tompkins, a friend and keen supporter of the Carnegie Corporation and its federation proposal, was one fall-out from the controversy. Bishop James Morrison, exasperated by his continued agitation for university federation, removed him from St. F. X. to run a parish in the fishing village of Canso. Tompkins’ presence there would later pay dividends for both the fishermen of Canso and the Antigonish Movement; however, the immediate result of the end of the federation debate was a temporary cessation of agitation for university extension work during the ‘cooling off’ period that followed. The federation controversy and involvement of the Carnegie Corporation also played a secondary, serendipitous role. On the eve of a trip to Truro to attend a meeting of the Nova Scotia Teachers Association, Rev. Dr. Moses Coady dined with the authors of the Learned-Sills Report in Antigonish. Kenneth C.M. Sills and William S. Learned told Coady they thought education was extremely important which helped change Coady’s attitude toward the association and strengthened his resolve to support it. Coady went to the meeting and talked himself into a job as organizer for a revitalized union and founding editor of its newsletter. His three-year stint with the teachers union raised his profile and improved his organizing skills; both things would be critical to his future leadership of the Antigonish Movement.

Early Development (1924 – 1930)

The 1st Rural Conference at St. F. X. in 1924 ushered in the second developmental stage of the Antigonish Movement. These conferences brought together diocesan priests and lay people concerned about the deteriorating socio-economic conditions of the diocese and region. The proceedings of the conferences, held annually between 1924 and 1928, were well publicized and widely discussed. The consistent call coming out of these conferences was for “immediate action!”; it was frequently suggested that one good place to begin was with adult education delivered through extension work. Meanwhile, Father Jimmy Tompkins continued his association with the Carnegie Corporation and in Canso got deeply involved with the plight of the fishermen. By 1927 there was powerful pressure on St. F. X. to formally undertake extension work. The Scottish Catholic Society of Canada continued to lobby hard for action. In Canso, a large meeting of fishermen in July aired their grievances and desperate situation; it made headlines around the country and underscored the plight of the fishing sector. Diocesan priests, at their annual retreat, strongly supported the fishermen and called on the government to respond. The St.F.X. Alumni Association was another body calling for action. By November 1928, it had succeeded in getting the Board of Governors “to approve the establishment of Extension Work along the lines suggested by the Alumni Committee,” and “…as soon as possible to provide a man for the carrying out of the work.” Dr. Moses Coady, a faculty member, was appointed founding Director of Extension and would later be joined by an assistant director Angus B (A.B.) MacDonald. Coady spent the first six months of 1928 traveling throughout Canada and the United States trying to come up with an affordable and effective program for extension work that would succeed in the local cultural context. Coady’s previous experience in youth and adult education, and his practical bent of mind favored the service-university models, like the University of Saskatchewan and the University of Wisconsin. These models disseminated knowledge to working people to help them solve concrete problems. Still, many questions remained unanswered when he returned in the late spring of 1929. The creation of the Extension Department at this time was purely formal; it had no budget and no staff and therefore was not operational. Meanwhile, the MacLean Commission investigating the east coast fisheries reported in July 1928. Coady made an important presentation to the Commission; he advocated for cooperatives and adult education and was thereafter appointed in early 1929 to organize the Maritime fishermen. Coady’s paid position with the government dovetailed nicely with his appointment as organizing Director of the Extension Department. While Coady undertook a ten-month organizing tour for a new fisheries union during the winter of 1929-30, the Scottish Catholic Society of Canada remained skeptical about the extent of the University’s commitment to the Extension Department. It had recently pushed ahead with plans for a fundraising campaign in support of a Rural-Industrial Improvement Commission and published a pamphlet, “Forward Nova Scotia”, in support of the campaign. With Coady set to finish his organizing tour with a inaugural conference of the new United Maritime Fishermen’s Union in June, St.F.X. finally approved a budget in the summer of 1930.