The Extension Department Takes Off (1930 – 1939)

The new Extension Department was founded with a budget of $10,000. This funding was supplemented the following year by a $10,000 grant from the American Carnegie Foundation, as well as further grants in subsequent years. A small staff was hired over the next few years. The Assistant Director, A.B. MacDonald, an agricultural specialist and educator with experience organizing farmers, left his position as Inspector of Schools for Antigonish-Guysborough and became a brilliant organizer and Coady’s right-hand man. Kay Thompson was hired in 1931 after Coady asked her to come back to Canada from New York and work as his general assistant. An excellent choice, she was a dedicated social reformer, superb journalist and skillful organizer. Alex S. MacIntyre, a former Cape Breton miner and militant unionist recently converted to the cooperative way, was recruited in 1932 to head the extension office in Glace Bay. He was visionary in his own right, but always clear-eyed about the realities and possibilities of the work. Other early figures from Extension’s first days were Ida Gallant (Delaney), Zita O’Hearn (Cameron), and Sister Marie Michael MacKinnon, a Sister of St. Martha. Gallant worked in Glace Bay while O’Hearn and Sister Marie Michael were based in Antigonish.

The new Extension Department was founded with a budget of $10,000. This funding was supplemented the following year by a $10,000 grant from the American Carnegie Foundation, as well as further grants in subsequent years. A small staff was hired over the next few years. The Assistant Director, A.B. MacDonald, an agricultural specialist and educator with experience organizing farmers, left his position as Inspector of Schools for Antigonish-Guysborough and became a brilliant organizer and Coady’s right-hand man. Kay Thompson was hired in 1931 after Coady asked her to come back to Canada from New York and work as his general assistant. An excellent choice, she was a dedicated social reformer, superb journalist and skillful organizer. Alex S. MacIntyre, a former Cape Breton miner and militant unionist recently converted to the cooperative way, was recruited in 1932 to head the extension office in Glace Bay. He was visionary in his own right, but always clear-eyed about the realities and possibilities of the work. Other early figures from Extension’s first days were Ida Gallant (Delaney), Zita O’Hearn (Cameron), and Sister Marie Michael MacKinnon, a Sister of St. Martha. Gallant worked in Glace Bay while O’Hearn and Sister Marie Michael were based in Antigonish.

After his return from the fact-finding mission, Coady and MacDonald began sketching out some ideas in a document called “Possible Activities of the Extension Department”. They decided to focus on the eastern counties of Nova Scotia and described the general purpose of the Extension Department as the improvement of the social, economic, educational and religious conditions of their people. They envisaged short courses, both cultural and vocational, leadership training courses, study clubs, correspondence courses, radio courses and industrial and folk schools. Information would be disseminated through letters, circulating libraries, local debates and public speaking competitions. They also planned to work with agencies already in the field and hoped to link the new extension work into an existing web of social organizations. They considered clergy, churches, government officials, agricultural representatives, existing co-operatives, community associations and professionals as partners in their work.

After his return from the fact-finding mission, Coady and MacDonald began sketching out some ideas in a document called “Possible Activities of the Extension Department”. They decided to focus on the eastern counties of Nova Scotia and described the general purpose of the Extension Department as the improvement of the social, economic, educational and religious conditions of their people. They envisaged short courses, both cultural and vocational, leadership training courses, study clubs, correspondence courses, radio courses and industrial and folk schools. Information would be disseminated through letters, circulating libraries, local debates and public speaking competitions. They also planned to work with agencies already in the field and hoped to link the new extension work into an existing web of social organizations. They considered clergy, churches, government officials, agricultural representatives, existing co-operatives, community associations and professionals as partners in their work.

To carry out this work, the Extension Department needed a variety of resources: periodicals for small circulating libraries, a clipping service, an open-shelf library, and a stenographer who could prepare study courses, reading guides and correspondence courses. During the first years, Coady and MacDonald were frequently on the road, organizing, leading, troubleshooting and distributing and gathering information; meanwhile the St.F.X. Extension office staff scrambled to keep up with the deluge of requests from Coady, MacDonald, and an ever-increasing number of inquirers.

The fieldworkers complemented the Extension Department office staff. Underpaid, overworked and understaffed, the fieldworkers put theory into practice by following up on openings created by Coady, MacDonald and others. Their typical duties included organizing and attending study clubs and meetings, identifying and training local leaders, and relaying information between the field and St.F.X.

Initially, the Extension Department relied heavily on the existing networks and resources of the Roman Catholic Church in Cape Breton and eastern Nova Scotia. Local priests, familiar with their own parishes, were enlisted to help advertise and organize initial town meetings. The first wave of study clubs were often formed in the parishes of priests who were members of the Scottish Catholic Society of Canada; evidently, their experience and interest in socio-economic matters helped the early work of the Extension Department. Coady would appear at these first meetings and proceed to “deconstruct” the plight of the people. He would use powerful and simple metaphors to explain how and why things had gotten so bad and then present cooperative organization as a way out. These “intellectual bombing runs” were meant to inspire and rouse the people, preparing for the creation of study clubs.

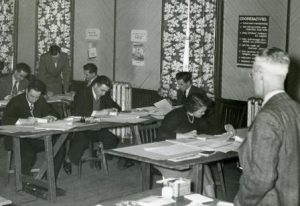

Local communities were organized into neighbourhood groups, usually composed of five to ten members who met in homes, halls and schoolhouses. Most communities would have several groups, and these “kitchen study clubs” became a distinctive feature of the Movement. Study clubs fostered a process whereby ordinary people, with the guidance of fieldworkers or others, read and studied on their own; they then brought back their ideas for debate and elaboration. The clubs studied various subjects – credit unions, cooperative methods, home economics, and farming and fishing techniques; the people decided what they wanted to learn about. As study and discussion proceeded, leaders would emerge who helped to initiate practical cooperative projects. These projects often succeeded because they were adapted to local circumstances and needs; furthermore, they had the support of the community.

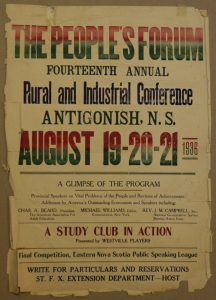

Sometimes the Extension Department would organize general meetings in parishes or communities, encouraging debate and discussions on larger issues. Occasional rallies based on combined annual meetings of different organizations brought Extension leaders and featured speakers into communities as well. The Extension Department relied enormously on volunteers; academics at St.F.X. gave short courses and contributed to newsletters and bulletins, local priests, ministers and other professionals in some places gave over large amounts of their time.

Sometimes the Extension Department would organize general meetings in parishes or communities, encouraging debate and discussions on larger issues. Occasional rallies based on combined annual meetings of different organizations brought Extension leaders and featured speakers into communities as well. The Extension Department relied enormously on volunteers; academics at St.F.X. gave short courses and contributed to newsletters and bulletins, local priests, ministers and other professionals in some places gave over large amounts of their time.

The Antigonish Movement’s growing needs and demands called for improvements in organization. Mimeographing thousands of pamphlets and sheets was deemed too time consuming. In 1933, staff began the The Extension Bulletin in order to provide a platform for debate, discussion and news. Five years later the The Extension Bulletin became the The Maritime Co-operator that carried for many years Coady’s column “The Anvil“. Extension began a “School for Leaders” in 1933 as the need for trained leaders became critical. While the Leaders’ School was a success, effective leaders and fieldworkers were always scarce during the early decades of the Antigonish Movement.

The years 1930 to 1935 were a take-off period. Between 1932 and 1935 study clubs increased from 179 to 940, club memberships from 1,500 to 10,650, and credit unions from 8 to 45. The Extension Department, with only five full-time and two-part time staff in 1935, had accomplished much with very little in a remarkably short period of time.