The Story Spreads

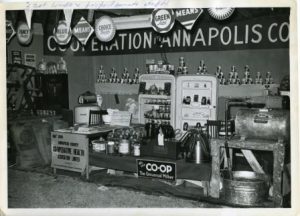

Initial successes in places like Larry’s River, Grand Étang, Havre Boucher and Canso, served examples of success for Coady and others as they delivered their cooperative message throughout the Maritimes. Coady proclaimed the great economic promise of cooperation and many heeded his call. By 1934, journalists, theologians, and others, many quite prominent in journalistic and literary circles, began to pick up the story and came to see and hear for themselves what the Antigonish Movement was about and marveled. Most were left-leaning progressives who were impressed by a movement that supported the working class and helped them help themselves without resorting to radicalism. As well, some were awe-struck that such a small group was accomplishing so much in the midst of the harsh economic depression and with little government help.

Initial successes in places like Larry’s River, Grand Étang, Havre Boucher and Canso, served examples of success for Coady and others as they delivered their cooperative message throughout the Maritimes. Coady proclaimed the great economic promise of cooperation and many heeded his call. By 1934, journalists, theologians, and others, many quite prominent in journalistic and literary circles, began to pick up the story and came to see and hear for themselves what the Antigonish Movement was about and marveled. Most were left-leaning progressives who were impressed by a movement that supported the working class and helped them help themselves without resorting to radicalism. As well, some were awe-struck that such a small group was accomplishing so much in the midst of the harsh economic depression and with little government help.

The Extension Department responded in two ways to these curious observers. First, they accommodated visitors by arranging interviews, visits and tours of cooperatives across eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton. Second, they often cringed as they read the over-enthusiastic and embellished media accounts that sometimes appeared; they tried to correct the most serious abuses of the truth.

About this time, the Antigonish Movement began to change from a local movement conceived and promoted by local individuals and inter-connected groups working for socio-economic uplift into a more diffuse, generalized movement that inspired individuals and associations of those seeking “social justice”. Just as visitors were drawn to Antigonish, Coady and MacDonald were pulled into contact with national and international organizations. Coady frequently traveled the international Roman Catholic circuit, speaking to U.S. organizations like the Catholic Rural Association and the National Catholic Welfare Conference. A second area of contact was the growing co-operative movement in the U.S. and Canada – the Co-operative League of the USA, the Ohio Farm Bureau and the Credit Union National Association in America, as well as the Co-operative Union of Canada, the Manitoba Pool Elevators, and the University of Alberta Extension Department. Evidently, adult education networks were growing in the US and Canada.

At the outbreak of war in 1939, the Antigonish Movement was enjoying both substantial organizational success and international recognition. The Movement had grown beyond the confines of its birthplace and appeared to be enjoying a golden age. However, Canada’s mobilization for war diverted precious manpower and financial resources from the Extension Department and the communities where its fieldworkers operated. Study clubs were still organized during the war, but on a much smaller scale. Conversely, World War II revitalized western capitalism. Therefore, just as the Antigonish Movement lost steam, it was forced to contend with invigorated capitalist enterprises, such as super markets and chain stores. Another mitigating factor was the very success of the Movement that forced Coady and others to focus on organizational development and the training of professional managers; these elite leaders were needed to deal with new economic and organizational complexities. However, it interposed a new layer between the common people and their institutions and undermined direct action. Finally, fieldworkers suffered from low pay, exhaustion and over-stretch. Although Coady used his scarce resources astutely, the system was always over-taxed; it forced Extension to rely on short courses to deliver the goods in many communities.

At the outbreak of war in 1939, the Antigonish Movement was enjoying both substantial organizational success and international recognition. The Movement had grown beyond the confines of its birthplace and appeared to be enjoying a golden age. However, Canada’s mobilization for war diverted precious manpower and financial resources from the Extension Department and the communities where its fieldworkers operated. Study clubs were still organized during the war, but on a much smaller scale. Conversely, World War II revitalized western capitalism. Therefore, just as the Antigonish Movement lost steam, it was forced to contend with invigorated capitalist enterprises, such as super markets and chain stores. Another mitigating factor was the very success of the Movement that forced Coady and others to focus on organizational development and the training of professional managers; these elite leaders were needed to deal with new economic and organizational complexities. However, it interposed a new layer between the common people and their institutions and undermined direct action. Finally, fieldworkers suffered from low pay, exhaustion and over-stretch. Although Coady used his scarce resources astutely, the system was always over-taxed; it forced Extension to rely on short courses to deliver the goods in many communities.

The 1950s and Beyond — Changing Times

The end of WWII and the return of reinvigorated consumer capitalism in the late 1940’s and 1950’s, together with the emergence of the modern welfare state and large-scale regional economic development schemes, signaled that the heyday of the Antigonish Movement was over. The Extension Department also now shared the field of economic and social development with numerous other educational agencies while new competitors in the retail sector challenged the consumer cooperatives. The Great Depression and acute parochialism of the 1930’s had given way to growth and increased penetration by outside business and media influences.

The end of WWII and the return of reinvigorated consumer capitalism in the late 1940’s and 1950’s, together with the emergence of the modern welfare state and large-scale regional economic development schemes, signaled that the heyday of the Antigonish Movement was over. The Extension Department also now shared the field of economic and social development with numerous other educational agencies while new competitors in the retail sector challenged the consumer cooperatives. The Great Depression and acute parochialism of the 1930’s had given way to growth and increased penetration by outside business and media influences.

The changing times, however, did not deter the Extension Department from thinking big ideas. Coady advocated for the appointment of union and labour representatives from central and western Canada to tie the Extension Department into national networks. The Department lobbied Bishop John R. MacDonald for more staff and experts to help deliver new programmes in labour, rural and urban education, land settlement, organic farming and various other sectors. By 1953, the Extension Department’s full and part-time staff numbered 25. Coady asked diocesan leaders who supported Extension work to meet regularly, reminding them of the earlier successful role of diocesan meetings like the rural and industrial conferences in maintaining the profile of the Extension Department and developing its future leaders.

Coady’s retirement in early 1952 due to ill health marked the end of an era, as he was in many ways and for many people the physical and spiritual embodiment of the Antigonish Movement. Coady’s vision and labour, in conjunction with a dedicated and exceptional staff, had led the Extension Department to concrete results in the economic sphere and created an intellectual and moral critique of the educational and economic status quo. This latter outcome of the Antigonish Movement was important because it introduced a healthy tension between the status quo and social action into St.F.X.’s educational mission. In addition, it provided the University with a valuable reservoir of public goodwill and public relations potential.

Rev. Michael J. MacKinnon replaced Coady as Director of Extension. The son of a coal miner from Sydney Mines, MacKinnon had worked most of his life in industrial Cape Breton and at the time of his appointment was head of the Sydney Extension office. MacKinnon’s tenure at the Extension Department saw mixed results. While he was intelligent and forceful, he at times lacked the diplomacy and prudence required to successfully navigate the changing and challenging currents of business, bureaucracy and public opinion. He was blamed for poisoning relations with the Nova Scotia Department of Agriculture during the creation of the highly touted Eastern Co-operative Services (ECS), a large-scale multi-department wholesale operation in Sydney. Ultimately dissatisfied with his performance, Bishop MacDonald had MacKinnon removed in 1958 and replaced him with Rev. John A. Gillis. Two years earlier, longtime Extension worker and associate director Alex Laidlaw had left the Extension Department to become general secretary of the Co-operative Union of Canada.

Rev. Gillis, a native of New Waterford, joined the Extension Department after serving in several rural and urban parishes, including Reserve Mines with Father Jimmy Tompkins, and had managed the university farm Mount Cameron. He immediately undertook a reappraisal of Extension’s programs and canvassed various parties for their input. The feedback suggested any great change to the direction of the Extension Department would be met with resistance. Yet he still hoped to update and improve the approaches used to deliver adult education so hired Dr. Remi Chiasson as a new associate director to help revitalize the Department. Under Gillis’s guidance the traditional programs in cooperative housing, consumer and producer cooperatives, labour education, fisheries, short courses and conferences were maintained as new initiatives were also pursued. Social and economic development work with First Nations reservations (Membertou, Eskasoni, and Pictou Landing) was initiated, woodlot owners organized, and a television station established. Unfortunately, both the woodlot owners group and the TV station did not last long while the flagship cooperative venture, ECS, also experienced difficulties. By 1961, Gillis beleaguered by these and internal staffing conflicts, resigned.

His successor, Rev. Joseph N. MacNeil, a deft diocesan administrator, brought a steady hand to the Extension Department, and, in spite of his lack of direct extension experience, he led successfully until 1969 when he was appointed Bishop of Saint John, NB. He too desired to maintain the traditional programs, but realizing that much of the work of the Department was becoming the mandate of government agencies, he also promoted more research and data collection on regional problems. Extension was in many ways moving away from actual participation in economic activities into research and policy development.

While MacNeil’s era at Extension coincided with a burst of interest in and funding for new research into development issues, it also witnessed a steep decline in the numbers of Maritimers employed in the traditional sectors of fishing, farming and forestry. Instead, there was an increase in the mining, manufacturing and service sectors, areas not traditionally the purview of Extension. The problem of how the Extension Department would remain relevant as new government agencies invaded its area of expertise, and fewer people worked in rural-based primary production, especially in northeastern Nova Scotia, remained a strategic concern. Thus, a trend to collaborate with government as a senior practitioner meshed with Extension’s move into analysis and policy. At the same time, MacNeil realized that collaboration might impact Extension’s independence and freedom to criticize.

From the 1960’s on fewer staff did less fieldwork. However, a steadfast commitment to adult education, public debate and solid policy and research initiatives, characterized the last thirty years of the Extension Department. The Extension Department changed and adapted as best it could within the context of the times and its institutional setting. During his time Director MacNeil had often been asked: “What is Extension up to?” It was an innocent question perhaps, but an exasperating one nonetheless that prompted him at one point to state the obvious: “It was unreasonable to expect the same public attention that was engendered in the Thirties and Forties when Extension was new and such a dynamic force.”

While the spirit and legacy of the Antigonish Movement thrives in many ways in the Maritimes and across Canada, an important international incarnation of the Movement was born just as the Extension Department’s golden years passed. By the end of World War II, thousands of people knew about the Movement in many places around the world. As more and more foreign students and observers came to St.F.X. to learn about co-operatives, credit unions and study clubs, the impetus grew to formalize the Movement’s philosophy and techniques for exportation internationally. Bishop John R. MacDonald, a long time supporter of Extension, along with Dr. Coady and assistant director Alex Laidlaw, began to think about establishing a new institute. It would be dedicated to educating foreign students in the Antigonish Movement in cooperation with Canadian and foreign aid programs. While these plans encountered stiff financial headwinds at first, the obstacles were surmounted and the creation of the Coady International Institute was announced in November, 1959.