The Impact of The Antigonish Movement

The Antigonish Movement, arising in the first decades of the 20th century in response to socio-economic decline in Maritime Canada, had by 1945 begun to demonstrate possible solutions to the problems of underdevelopment in distant lands. Throughout the years, it has touched the lives of thousands of people in Canada and abroad, and today, some 80 years later, especially through the Coady International Institute, it continues to promote democratically-based and locally-organized grassroots cooperative action in many parts of the world. The impact of the Antigonish Movement unfolds in many different ways, but the most important influence has always been the change it effects within the hearts and minds of people as thought and imagination become actively engaged in social action through adult education.

Beginning in the 1920s with both the publication of Fr. Jimmy Tompkins’ famous pamphlet Knowledge for the People and the opening of the People’s Schools at St.F.X. University, citizens, mainly from the Diocese of Antigonish, were inspired and empowered through adult education. With the establishment of the Extension Department in 1928, many more people from across northeastern Nova Scotia and beyond became committed co-operators through membership in study clubs and as users of the valuable services and information delivered by the Extension Department and its supporters. In 1959, the establishment of the Coady International Institute formally propelled this strategy of mobilizing the people into the international arena.

Beginning in the 1920s with both the publication of Fr. Jimmy Tompkins’ famous pamphlet Knowledge for the People and the opening of the People’s Schools at St.F.X. University, citizens, mainly from the Diocese of Antigonish, were inspired and empowered through adult education. With the establishment of the Extension Department in 1928, many more people from across northeastern Nova Scotia and beyond became committed co-operators through membership in study clubs and as users of the valuable services and information delivered by the Extension Department and its supporters. In 1959, the establishment of the Coady International Institute formally propelled this strategy of mobilizing the people into the international arena.

The impact is also reflected in the large number of organizations and institutions which owe their genesis in some way to the Antigonish Movement. Credit unions, and co-operatives of many varieties – housing, producer, marketing and consumer – were directly created from the study clubs of the Antigonish Movement. A number of labour organizations – trade unions and union associations – also owe their existence to the movement. Moreover, Nova Scotia’s regional library system is indebted to visionaries like Father Jimmy Tompkins.

The impact is also reflected in the large number of organizations and institutions which owe their genesis in some way to the Antigonish Movement. Credit unions, and co-operatives of many varieties – housing, producer, marketing and consumer – were directly created from the study clubs of the Antigonish Movement. A number of labour organizations – trade unions and union associations – also owe their existence to the movement. Moreover, Nova Scotia’s regional library system is indebted to visionaries like Father Jimmy Tompkins.

Leadership development has always been a central concern of the Movement since adult education in the socio-economic sphere is primarily about empowering people to effect change themselves. Successful change requires inspirational leaders. The founders of the Movement not only modeled leadership, but also helped to establish and then play important leading roles in many national and international organizations. Thus, they demonstrated leadership that attempted to maximize the influence of useful ideas. Of course, the Movement produced many second and third generation leaders who followed in the footsteps of the pioneers as they pursued worthwhile projects on the global stage. Finally, the careers of many men and women who were not formally part of the Antigonish Movement have been inspired and shaped by the ideas and deeds of its leaders.

Local/Regional

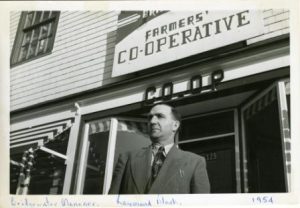

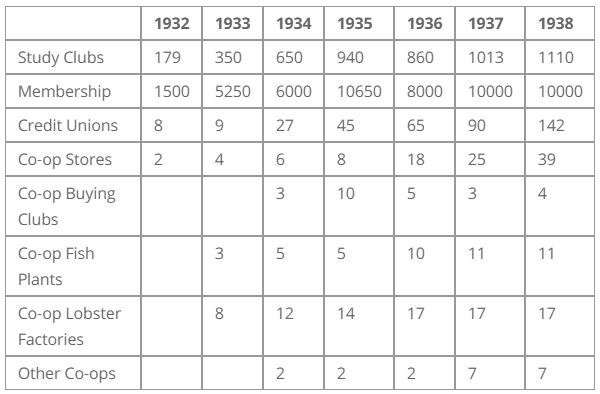

The local and regional impact of the Antigonish Movement was powerful, especially during the 1930s and early 1940s when the region grappled with severe economic problems. First, people like Father Jimmy Tompkins and Dr. Moses Coady provided a vision of hope, self-help and mutual cooperation when the response of traditional institutions was insufficient or non-existent. Their provision of technique and stress on self-agency at a time when most workers had little education should not be underestimated. In the words of pioneer fieldworker Ida Delaney: “There was a personal enrichment brought into the lives of those who participated…. The study clubs gave men and women a way to continue the education that had been abruptly cut off when they left school.” This consciousness-raising process is demonstrated by the life of Claire Gillis from the coal-mining region of Cape Breton who advanced far beyond his Grade 4 education by participating enthusiastically in the Movement; ultimately, he strongly influenced the coal miners and became a social reformer and Member of Parliament. Second, the Movement created significant economic assets that directly benefited those most in need. During the 1920’s and 1930s, when government and commerce retrenched, withdrew and exploited, the credit union and cooperative ideas represented practical solutions that people could implement to their own benefit. From about 1930 to the first years of World War II, these community-based institutions were an important positive impact on the regional economy. The table below provides an overview of the rapid regional growth of study clubs, credit unions and cooperatives during the 1930s.

The local and regional impact of the Antigonish Movement was powerful, especially during the 1930s and early 1940s when the region grappled with severe economic problems. First, people like Father Jimmy Tompkins and Dr. Moses Coady provided a vision of hope, self-help and mutual cooperation when the response of traditional institutions was insufficient or non-existent. Their provision of technique and stress on self-agency at a time when most workers had little education should not be underestimated. In the words of pioneer fieldworker Ida Delaney: “There was a personal enrichment brought into the lives of those who participated…. The study clubs gave men and women a way to continue the education that had been abruptly cut off when they left school.” This consciousness-raising process is demonstrated by the life of Claire Gillis from the coal-mining region of Cape Breton who advanced far beyond his Grade 4 education by participating enthusiastically in the Movement; ultimately, he strongly influenced the coal miners and became a social reformer and Member of Parliament. Second, the Movement created significant economic assets that directly benefited those most in need. During the 1920’s and 1930s, when government and commerce retrenched, withdrew and exploited, the credit union and cooperative ideas represented practical solutions that people could implement to their own benefit. From about 1930 to the first years of World War II, these community-based institutions were an important positive impact on the regional economy. The table below provides an overview of the rapid regional growth of study clubs, credit unions and cooperatives during the 1930s.

The work of Dr. Moses Coady, Father Jimmy Tompkins and A.B. MacDonald in Extension and the broader movement was to lead or assist in the creation of many important institutions. In 1921, Coady began to organize the Nova Scotia Teacher’s Union and started its newsletter. Today, the union is one of the strongest in the province. As well, Coady’s epic organizing tour in the winter of 1929-30 led to the creation of the United Maritime Fishermen’s Union that improved the lot of the inshore fishers by providing a regional network of cooperative associations. A.B. MacDonald was the managing director of the Nova Scotia Credit Union League since its inception in 1934. He and other organizers helped start the Canadian Livestock Cooperative in Moncton, New Brunswick with its two branches in Nova Scotia – the Canadian Livestock Co-operative in Sydney and Eastern Co-operative Services in Antigonish. Tompkins returned from Britain and the US with inspirational ideas about adult education and went on to become a founding member of the Canadian Association for Adult Education (CAAE). Perhaps his most enduring impact was his role in bringing libraries and housing cooperatives to the common people of Nova Scotia. He attracted two talented women to the cause, Sister Frances Dolores, SC, and Mary Arnold. Sister Dolores helped to start the regional library system, and Mary Arnold wrote legislation and helped local housing cooperators execute their vision in Reserve Mines.  The success of the housing cooperative in Reserve Mines sparked many similar endeavours in Sydney, Whitney Pier, Glace Bay and other locales across Nova Scotia. At the end of World War II, there were 71 completed co-op houses in the Maritimes and another 171 under construction. By 1978, 2000 families were living in co-operatively constructed or improved houses throughout the Maritimes. Joe Laben, a miner, one of the original housing cooperators in Reserve Mines, eventually worked for the St.F.X. Extension Department for eighteen years and was nationally recognized as a pioneer in the field. Leadership by example has been a staple in the Antigonish Movement as new generations have been inspired by the vision of its founders. Today, economic development organizations such as New Dawn Enterprises, Ltd. (housing, medical services, community organization support services), the Seton Foundation (social housing) and Cape Breton University’s Tompkins Institute for Human Values and Technology (community capital fund) in Cape Breton can trace their lineage directly back to the Movement. The same is true for scores of successful credit unions across the Maritimes, such as the Bergengren Credit Union in Antigonish, named after the American credit union expert Roy Bergengren who Tompkins invited to speak at a Rural and Industrial conference in 1931. His speech launched this most vital aspect of the Extension program locally and through the Coady International Institute eventually into the world beyond. The Antigonish Movement also touched the lives of Nova Scotia’s First Nations, the Mi’kmaq, when Extension Department fieldworkers began working in Cape Breton during the 1950s. Initially, the Mi’kmaq were suspicious and reserved, but as they began to work together on small projects that produced immediate tangible results such as organizing fundraising dances and socials, they were encouraged to tackle larger ones like housing. Extension helped get native children enrolled in local schools for the first time and by the late 1970s some of those had gone on to attend post-secondary colleges. Extension’s work on the Cape Breton native reserves, and in the Black communities of northeastern Nova Scotia, highlights again the Department’s desire to develop leaders who would be able to take charge of their community’s own destiny. For example, at one time, Extension’s Sydney office had two natives on staff. The jobs themselves were not as important as the training they provided; one of the native workers went on to become the first president of the Union of Nova Scotia Indians and the other became editor of The Micmac News.

The success of the housing cooperative in Reserve Mines sparked many similar endeavours in Sydney, Whitney Pier, Glace Bay and other locales across Nova Scotia. At the end of World War II, there were 71 completed co-op houses in the Maritimes and another 171 under construction. By 1978, 2000 families were living in co-operatively constructed or improved houses throughout the Maritimes. Joe Laben, a miner, one of the original housing cooperators in Reserve Mines, eventually worked for the St.F.X. Extension Department for eighteen years and was nationally recognized as a pioneer in the field. Leadership by example has been a staple in the Antigonish Movement as new generations have been inspired by the vision of its founders. Today, economic development organizations such as New Dawn Enterprises, Ltd. (housing, medical services, community organization support services), the Seton Foundation (social housing) and Cape Breton University’s Tompkins Institute for Human Values and Technology (community capital fund) in Cape Breton can trace their lineage directly back to the Movement. The same is true for scores of successful credit unions across the Maritimes, such as the Bergengren Credit Union in Antigonish, named after the American credit union expert Roy Bergengren who Tompkins invited to speak at a Rural and Industrial conference in 1931. His speech launched this most vital aspect of the Extension program locally and through the Coady International Institute eventually into the world beyond. The Antigonish Movement also touched the lives of Nova Scotia’s First Nations, the Mi’kmaq, when Extension Department fieldworkers began working in Cape Breton during the 1950s. Initially, the Mi’kmaq were suspicious and reserved, but as they began to work together on small projects that produced immediate tangible results such as organizing fundraising dances and socials, they were encouraged to tackle larger ones like housing. Extension helped get native children enrolled in local schools for the first time and by the late 1970s some of those had gone on to attend post-secondary colleges. Extension’s work on the Cape Breton native reserves, and in the Black communities of northeastern Nova Scotia, highlights again the Department’s desire to develop leaders who would be able to take charge of their community’s own destiny. For example, at one time, Extension’s Sydney office had two natives on staff. The jobs themselves were not as important as the training they provided; one of the native workers went on to become the first president of the Union of Nova Scotia Indians and the other became editor of The Micmac News.

National

The persons and ideas of the Antigonish Movement have played a strong role in many national organizations and endeavours. A.B. MacDonald, the assistant director of Extension, left in 1943 to become the national secretary of the Co-operative Union of Canada [CUC], the national voice of credit unions. At the CUC, MacDonald worked on several important projects, and in assuming the mantle of national leadership, extended the vision of the Antigonish Movement across Canada. MacDonald also introduced Cooperatives for American Remittances to Europe (C.A.R.E) to Canada and for two years was national chairman of the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. Coady, in the last two decades of his life during the 1940s and 1950s, spoke at countless national-level meetings and conferences. In 1949, he was elected president of the CAAE and was later succeeded by Alex Laidlaw who had replaced MacDonald as the assistant director of Extension in 1944. From its early days, Extension provided expertise and assistance to hundreds of requests for help from other Canadian organizations. This important support work resulted in significant gains for the cooperative movement. For instance, Norman Mackenzie, a young divinity student at the University of Toronto, decided to do graduate work in cooperatives. He wrote to Extension and was assigned to work in the Cape Breton Highlands for a year. Then, when the Extension Department of the University of British Columbia was looking for someone to organize credit unions, MacKenzie was invited to Prince Rupert. There he helped set up a successful credit union which financed a fisherman’s co-op which went on to grow into a west coast version of the United Maritime Fishermen. Credit unions took hold in BC where one of the world’s largest, VanCity, now prospers. The Antigonish Movement greatly benefited the labour movement. One example is John Delaney (husband of Ida Delaney) who as a young man was a charter member and director of the Glace Bay Central Credit Union. In 1950, he was elected an International Board Member for District 26 of the United Mine Workers of America and later held high administrative positions at the national and international levels. As well, he was a member of the Medicare Commission appointed to advise the federal government on the creation of its public medical system in the 1960s. In the early 1970s, the Extension Department helped launch the Atlantic Regional Labour Education Centre. ARLEC sought to improve the social knowledge, communication skills and self-confidence of unionists through an eight-week summer course held at St.F.X. Many ARLEC graduates translated their training into new careers. In 1977, 67 delegates to the Canadian Labour Congress convention and 10 provincial political candidates in Newfoundland were ARLEC alumni. Another testament to ARLEC’s effectiveness, and the ongoing impact of the Antigonish Movement, was the prominent role an ARLEC graduate played in the Newfoundland asbestos workers’ fight for better health conditions.

International

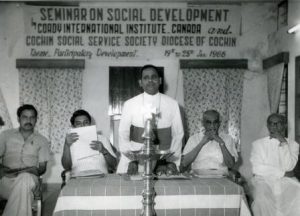

The international impact of the Antigonish Movement really began in the mid-1930s. As word spread about the Extension Department’s successes, a host of influential visitors came to Nova Scotia to see and learn firsthand about its work. Many visitor-observers were contacts of Father Jimmy Tompkins; they in turn brought others. In addition, Dr. Moses Coady was frequently invited to speak in the US, and in 1936, the Carnegie Foundation and the National Catholic Welfare Conference sponsored his twelve-city lecture tour. As well, The New York Times, The London Times and The BBC ran features on the Movement. The techniques and ideas of the Antigonish Movement were thus widely disseminated and became influential in the US and beyond. For example, the Ohio Farm Bureau and the Cooperative League of America sent representatives to Antigonish who ultimately adopted some of its practices. Further afield, two Australians, Kevin Yates and Father John Gallagher, who came through Antigonish during the mid-1940s, returned “down under” and implemented the Extension program there. Today, Yates is considered the founder of credit unions in Australia. Between 1946 and 1960, some 275 men from Pakistan, India and Indonesia came to Antigonish to learn about the Antigonish Movement. These students returned to their home countries and carried the message of the Extension program far from Antigonish.

The international impact of the Antigonish Movement really began in the mid-1930s. As word spread about the Extension Department’s successes, a host of influential visitors came to Nova Scotia to see and learn firsthand about its work. Many visitor-observers were contacts of Father Jimmy Tompkins; they in turn brought others. In addition, Dr. Moses Coady was frequently invited to speak in the US, and in 1936, the Carnegie Foundation and the National Catholic Welfare Conference sponsored his twelve-city lecture tour. As well, The New York Times, The London Times and The BBC ran features on the Movement. The techniques and ideas of the Antigonish Movement were thus widely disseminated and became influential in the US and beyond. For example, the Ohio Farm Bureau and the Cooperative League of America sent representatives to Antigonish who ultimately adopted some of its practices. Further afield, two Australians, Kevin Yates and Father John Gallagher, who came through Antigonish during the mid-1940s, returned “down under” and implemented the Extension program there. Today, Yates is considered the founder of credit unions in Australia. Between 1946 and 1960, some 275 men from Pakistan, India and Indonesia came to Antigonish to learn about the Antigonish Movement. These students returned to their home countries and carried the message of the Extension program far from Antigonish.  This growing influx of observers and students occasioned the creation of the Coady International Institute [The Coady] in 1959. In addition to its diploma and certificate programs offered at St.F.X. in Antigonish, The Coady offered short courses and consultations in Africa, the Indian sub-continent, southeast Asia and the Caribbean. The impact of the Coady is impossible to measure comprehensively, but a window on its scope is opened by the 1978 travel itinerary of its director Father George Topshee. Starting in Seoul, he traveled through Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines, Sri Lanka and India. Along the way, he toured credit unions, craft co-ops and study clubs, many of them the creations of Coady graduates. He personally met nine alumni and recorded an impressive, firsthand account of their accomplishments. One in particular stands out. He visited a stone quarry outside of Bangalore, India where 40,000 souls laboured as “bonded” workers. They were de facto slaves of the owners of their debts and lived in terrible conditions. A Coady graduate, Joe Ulahanan, and Father Harry Stocks were attempting to start a co-operative quarry that would break the workers’ bondage. Father Harry and Joe were able, after organizing an association of 4,000 workers, to obtain the lease for four quarries. They went to organize co-ops to run the quarries, build housing, start credit unions and stores. How could one measure the impact of freeing just one of those workers and their families from that deplorable circumstance? By 1984, Coady staff and alumni had established 49 development centres and agencies across Africa, Asia and Latin America that retained links to the Institute.

This growing influx of observers and students occasioned the creation of the Coady International Institute [The Coady] in 1959. In addition to its diploma and certificate programs offered at St.F.X. in Antigonish, The Coady offered short courses and consultations in Africa, the Indian sub-continent, southeast Asia and the Caribbean. The impact of the Coady is impossible to measure comprehensively, but a window on its scope is opened by the 1978 travel itinerary of its director Father George Topshee. Starting in Seoul, he traveled through Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines, Sri Lanka and India. Along the way, he toured credit unions, craft co-ops and study clubs, many of them the creations of Coady graduates. He personally met nine alumni and recorded an impressive, firsthand account of their accomplishments. One in particular stands out. He visited a stone quarry outside of Bangalore, India where 40,000 souls laboured as “bonded” workers. They were de facto slaves of the owners of their debts and lived in terrible conditions. A Coady graduate, Joe Ulahanan, and Father Harry Stocks were attempting to start a co-operative quarry that would break the workers’ bondage. Father Harry and Joe were able, after organizing an association of 4,000 workers, to obtain the lease for four quarries. They went to organize co-ops to run the quarries, build housing, start credit unions and stores. How could one measure the impact of freeing just one of those workers and their families from that deplorable circumstance? By 1984, Coady staff and alumni had established 49 development centres and agencies across Africa, Asia and Latin America that retained links to the Institute.  The original inspiration and purpose of the Antigonish Movement still informs The Coady today as it carries out “traditional” agricultural and rural development work through partnerships with organizations like the Southeast Asia Rural Social Leadership Institute (SEARSOLIN) in the Philippines. Meanwhile, The Coady has adapted to current realities and new localities. Today, The Coady partners with organizations designed to assist in small-scale capital formation and entrepreneurship. Together with the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) and the Friends of Women’s World Banking in India, it is developing the innovative Indian School of Microfinance for Women (ISMFW) in Ahmedabad, India. The ISMFW is designed to fill the gap between the established financial institutions and the millions of people – mostly women – who lack access to basic financial services. In 2009, the Coady International Institute works in many sectors, such as civil society, strengthening community initiatives and institutions. It also promotes peace-building in war-torn countries, and encourages the development of community-based assets among Canada’s First Nations and other indigenous people around the world. Wherever its staff and alumni are found, however, they continue to aim the inspirational message of the Antigonish Movement at the same target that Coady and Tompkins had aimed at in the 1920s and 1930s – the hearts, minds and imagination of the common people. A strong impact has always been the dynamic of the movement’s influence and achievements at the regional, national, and global levels.

The original inspiration and purpose of the Antigonish Movement still informs The Coady today as it carries out “traditional” agricultural and rural development work through partnerships with organizations like the Southeast Asia Rural Social Leadership Institute (SEARSOLIN) in the Philippines. Meanwhile, The Coady has adapted to current realities and new localities. Today, The Coady partners with organizations designed to assist in small-scale capital formation and entrepreneurship. Together with the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) and the Friends of Women’s World Banking in India, it is developing the innovative Indian School of Microfinance for Women (ISMFW) in Ahmedabad, India. The ISMFW is designed to fill the gap between the established financial institutions and the millions of people – mostly women – who lack access to basic financial services. In 2009, the Coady International Institute works in many sectors, such as civil society, strengthening community initiatives and institutions. It also promotes peace-building in war-torn countries, and encourages the development of community-based assets among Canada’s First Nations and other indigenous people around the world. Wherever its staff and alumni are found, however, they continue to aim the inspirational message of the Antigonish Movement at the same target that Coady and Tompkins had aimed at in the 1920s and 1930s – the hearts, minds and imagination of the common people. A strong impact has always been the dynamic of the movement’s influence and achievements at the regional, national, and global levels.